Next: §25 Curved jets Previous: §23 Prandtl-Meyer flow Contents

Let us consider now the two dimensional problem of steady plane

parallel flow at infinity which turns through an angle as it flows round

a curved profile. A particular case of this problem occurs when the flow

turns through an angle (Landau & Lifshitz, 1995). For this particular situation the

Prandtl-Meyer flow is obviously the solution and so, the hydrodynamical

quantities depend on a single variable, the angle ![]() measured

from a defined axis at the onset of the curvature. Because of this,

all quantities can be expressed as functions of each other. Since this

case is a particular solution to the general problem, it is natural to

seek the solutions of the equations of motion in which the quantities

measured

from a defined axis at the onset of the curvature. Because of this,

all quantities can be expressed as functions of each other. Since this

case is a particular solution to the general problem, it is natural to

seek the solutions of the equations of motion in which the quantities

![]() can be expressed as a function of each other.

Evidently this imposes a restriction on the solution of the equations

of motion since for two dimensional flow, any quantity depends on two

coordinates,

can be expressed as a function of each other.

Evidently this imposes a restriction on the solution of the equations

of motion since for two dimensional flow, any quantity depends on two

coordinates, ![]() and

and ![]() , and so any chosen hydrodynamical variable

can be written as a function of any other two.

, and so any chosen hydrodynamical variable

can be written as a function of any other two.

Because of the fact that the flow is uniform at infinity, where all quantities are constant, particularly the entropy, and because the flow is steady, the entropy is constant along a streamline. Thus, if there are no shock waves in the flow, the entropy remains constant along the whole trajectory of the flow and in what follows we will use this result.

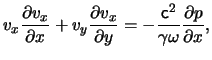

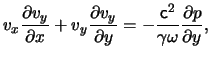

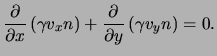

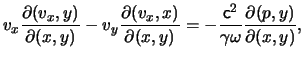

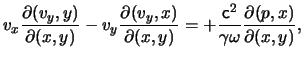

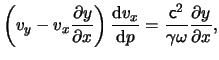

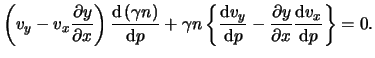

In this case, Euler's equation, eq.(9.7), and the continuity equation, eq.(9.1), are respectively:

|

|

|

|

|

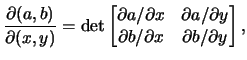

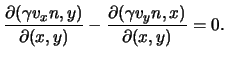

Rewriting these equations as Jacobians we obtain:

|

|

|

|

|

We now take the coordinate ![]() and the pressure

and the pressure ![]() as

independent variables. To make this transformation we have to multiply

the previous set of equations by

as

independent variables. To make this transformation we have to multiply

the previous set of equations by

![]() . This multiplication leaves the equations the same, but with the

substitution

. This multiplication leaves the equations the same, but with the

substitution

![]() .

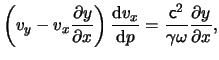

Expanding this last relation and because all quantities are now functions

of the pressure

.

Expanding this last relation and because all quantities are now functions

of the pressure ![]() but not of x, it follows that:

but not of x, it follows that:

|

|

|

|

|

Here we have taken

![]() to mean the derivative

at constant pressure:

to mean the derivative

at constant pressure:

![]() . Since every

hydrodynamic quantity is assumed to be a function of the pressure,

then in the previous set of equations it necessarily follows that

. Since every

hydrodynamic quantity is assumed to be a function of the pressure,

then in the previous set of equations it necessarily follows that

![]() is a function which depends only on the pressure,

that is

is a function which depends only on the pressure,

that is

![]() . Therefore:

. Therefore:

No further calculations are needed if we use the solution for the

case in which a rarefaction wave is formed when flow turns around

an angle (Landau & Lifshitz, 1995). This solution is given by the results of

section §23. As was mentioned in that section, all

hydrodynamical quantities are constant along the characteristic lines

![]() . This particular solution of the flow

past an angle obviously corresponds to the case in which

. This particular solution of the flow

past an angle obviously corresponds to the case in which

![]() in eq.(24.1). The function

in eq.(24.1). The function ![]() is determined

from the equations obtained in section §23.

is determined

from the equations obtained in section §23.

For a given constant value of the pressure ![]() , eq.(24.1),

gives a set of straight lines in the

, eq.(24.1),

gives a set of straight lines in the

![]() -

-![]() plane.

These lines intersect the streamlines at the Mach angle. This is due

to the fact that the lines

plane.

These lines intersect the streamlines at the Mach angle. This is due

to the fact that the lines

![]() for the particular

solution of the flow through an angle have this property. In other

words, one family of characteristic surfaces correspond to a set of

straight lines along which all quantities remain constant. However,

for the general case, this lines are no longer concurrent.

for the particular

solution of the flow through an angle have this property. In other

words, one family of characteristic surfaces correspond to a set of

straight lines along which all quantities remain constant. However,

for the general case, this lines are no longer concurrent.

The properties of the flow as described above are analogous to the non-relativistic equivalent known as simple waves (Landau & Lifshitz, 1995). In what follows we will use this name to refer to such a flow.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.90]{fig.4.2.eps}](img682.png)

|

Let us now construct the solution for a simple wave once a fixed

profile is given. Consider the profile as shown in fig.(IV.1).

Plane parallel steady flow streams from the left of the point O and flows around

the given profile. Since we assume that the flow is supersonic,

the effect of the curvature starting at O is communicated to the

flow only downstream of the characteristic OA generated at point O. The

characteristics to the left of OA, region 1, are all parallel

and intersect the ![]() axis at the Mach Angle

axis at the Mach Angle ![]() given

by eq.(11.20):

given

by eq.(11.20):

where the velocity

![]() is the velocity of the flow to the

left of the characteristic OA. In eqs.(23.11)-(23.18)

the angle

is the velocity of the flow to the

left of the characteristic OA. In eqs.(23.11)-(23.18)

the angle ![]() of the characteristics is measured with respect

to some straight line in the

of the characteristics is measured with respect

to some straight line in the

![]() -

-![]() plane. As a result,

we can choose for those equations the constant of integration

plane. As a result,

we can choose for those equations the constant of integration

![]() This means that the line from which the

angle

This means that the line from which the

angle ![]() is measured has been chosen in a very particular way.

In order to find the line which is the characteristic for

is measured has been chosen in a very particular way.

In order to find the line which is the characteristic for

![]() , let us proceed as follows. When

, let us proceed as follows. When

![]() and the gas

is ultrarelativistic, eqs.(23.13)-(23.14) show that the

velocity

and the gas

is ultrarelativistic, eqs.(23.13)-(23.14) show that the

velocity

![]() and for the classical case, it follows from

eqs.(23.17)-(23.18) that the velocity takes the value

and for the classical case, it follows from

eqs.(23.17)-(23.18) that the velocity takes the value

![]() . In both cases this means that the line

. In both cases this means that the line

![]() corresponds to the point at which the flow has reached the value

of the local velocity of sound. This, however, is not possible since

we are assuming that the flow is supersonic everywhere. Nevertheless,

if the rarefaction wave is assumed to extend formally into the region to

the left of OA, we can use these relations and then the characteristic

line must correspond to a value of

corresponds to the point at which the flow has reached the value

of the local velocity of sound. This, however, is not possible since

we are assuming that the flow is supersonic everywhere. Nevertheless,

if the rarefaction wave is assumed to extend formally into the region to

the left of OA, we can use these relations and then the characteristic

line must correspond to a value of ![]() given by:

given by:

for the ultrarelativistic case according to eq.(23.7),

eq.(23.10) and eq.(23.12). The angle between the

characteristics and the ![]() axis is then given by:

axis is then given by:

![]() , where

, where

![]() and the angle

and the angle ![]() is the Mach angle in region 1. The

is the Mach angle in region 1. The

![]() and

and ![]() velocity components in terms of the azimuthal angle

velocity components in terms of the azimuthal angle ![]() are

given by:

are

given by:

and the values for the magnitude of the velocity, the angle ![]() and the pressure are given by:

and the pressure are given by:

for a classical gas according to

eqs.(23.15)-(23.18) and using the fact that the Poisson

adiabatic for a polytropic gas means that:

![]() . In the case of an

ultrarelativistic gas, eqs.(23.12)-(23.14) together

with Bernoulli's equation and the fact that the enthalpy density

. In the case of an

ultrarelativistic gas, eqs.(23.12)-(23.14) together

with Bernoulli's equation and the fact that the enthalpy density

![]() give:

give:

Since the angle

![]() is the angle between the

characteristics and the

is the angle between the

characteristics and the ![]() axis, it follows that the line describing

the characteristics is:

axis, it follows that the line describing

the characteristics is:

The function ![]() is obtained from the following arguments for a

given profile of the curvature (Landau & Lifshitz, 1995). If the equation describing

the shape of the profile is given by the points

is obtained from the following arguments for a

given profile of the curvature (Landau & Lifshitz, 1995). If the equation describing

the shape of the profile is given by the points

![]() and

and ![]() where

where

![]() , the velocity of the gas is tangential to

this surface, and so:

, the velocity of the gas is tangential to

this surface, and so:

Now, the equation of the line through the point ![]() which

makes an angle

which

makes an angle

![]() with the

with the ![]() axis is:

axis is:

Eq.(24.14) is the same as eq.(24.12) if we set:

If we start from a given profile

![]() then, using eq.(24.13) we can find the parametric set of

equations:

then, using eq.(24.13) we can find the parametric set of

equations:

![]() and

and ![]() .

Substitution of

.

Substitution of

![]() from eq.(24.7)

or eq.(24.10) depending of whether the gas is classical or

ultrarelativistic, we find

from eq.(24.7)

or eq.(24.10) depending of whether the gas is classical or

ultrarelativistic, we find

![]() and

and ![]() . Substitution of this in eq.(24.15) gives the required

function

. Substitution of this in eq.(24.15) gives the required

function ![]() .

.

If the shape of the surface around which the gas flows around is convex,

the angle ![]() that the velocity vector makes with the

that the velocity vector makes with the ![]() axis decreases downstream. The angle

axis decreases downstream. The angle

![]() between the

characteristics leaving the surface and the

between the

characteristics leaving the surface and the ![]() axis also decreases

monotonically. In other words, characteristics for this kind of

flow do not intersect and we form a continuous and rarefied flow.

axis also decreases

monotonically. In other words, characteristics for this kind of

flow do not intersect and we form a continuous and rarefied flow.

On the other hand, if the shape of the surface is concave as shown in

fig.(IV.2), the angle ![]() increases monotonically

and so does the angle the characteristics make with the

increases monotonically

and so does the angle the characteristics make with the ![]() axis. This means that there must exist a region in the flow in which

characteristics intersect. The value of the hydrodynamical quantities

is constant for every characteristic line. This constant however

changes for different non-parallel characteristics. In other words,

at the point of intersection different hydrodynamical quantities -for

example, the pressure- are multivalued. This situation can not occur

and results in the formation of a shock wave. This shock wave cannot

be calculated from the above considerations, since they were based on

the assumption that the flow had no discontinuities at all -the entropy

was assumed to be constant. However, the point at which the shock wave

starts, that is point K in fig.(IV.2), can be calculated from

the following considerations. We can work out the inclination of the

characteristics

axis. This means that there must exist a region in the flow in which

characteristics intersect. The value of the hydrodynamical quantities

is constant for every characteristic line. This constant however

changes for different non-parallel characteristics. In other words,

at the point of intersection different hydrodynamical quantities -for

example, the pressure- are multivalued. This situation can not occur

and results in the formation of a shock wave. This shock wave cannot

be calculated from the above considerations, since they were based on

the assumption that the flow had no discontinuities at all -the entropy

was assumed to be constant. However, the point at which the shock wave

starts, that is point K in fig.(IV.2), can be calculated from

the following considerations. We can work out the inclination of the

characteristics ![]() as a function of the coordinates

as a function of the coordinates

![]() and

and ![]() . This function

. This function ![]() becomes multivalued when these

coordinates exceed certain fixed values, say

becomes multivalued when these

coordinates exceed certain fixed values, say

![]() and

and ![]() .

At a fixed

.

At a fixed

![]() the curve giving the value of

the curve giving the value of ![]() as a function of

as a function of ![]() becomes multivalued. That is, the derivative

becomes multivalued. That is, the derivative

![]() , or

, or

![]() . It is evident

that at the point

. It is evident

that at the point

![]() the curve

the curve ![]() must lie

in both sides of the vertical tangent, else the function

must lie

in both sides of the vertical tangent, else the function ![]() would already be multivalued. This means that the point

would already be multivalued. This means that the point ![]() cannot be a maximum, or a minimum of the function

cannot be a maximum, or a minimum of the function ![]() but it has to be an inflection point. In other words, the coordinates

of point K in fig.(IV.2) can be calculated from the set of

equations (Landau & Lifshitz, 1995):

but it has to be an inflection point. In other words, the coordinates

of point K in fig.(IV.2) can be calculated from the set of

equations (Landau & Lifshitz, 1995):

When the profile is concave, the streamlines that pass above the point O in fig.(IV.2) pass through a shock wave and the simple wave no longer exist. Streamlines that pass below this point seem to be safe from destruction. However, the perturbing effect from the shock wave KL influences this region also, and so it is not possible to describe the flow there as a simple wave. Nevertheless, since the flow is supersonic, the perturbing effect of the shock wave is only communicated downstream. This means that the region to the left of the characteristic PK (which corresponds to the other set of characteristics emanating from point P) does not notice the presence of the shock wave. In other words, the solution mentioned above, in which a simple wave is formed around a concave profile is only valid to the left of the segment PKL.