Next: §10 Classical equations of Previous: §8 Energy-momentum tensor in Contents

The conservation of mass in the absence of any sinks or sources is described by the relativistic continuity equation (Landau & Lifshitz, 1995):

where the particle flux 4-vector

![]() and the scalar

and the scalar ![]() is the proper number density of particles in

the fluid. The energy-momentum tensor in eq.(8.4) does not

take into account any dissipative processes and therefore the equations

of motion expressed by eq.(8.1) refer to an ideal fluid.

is the proper number density of particles in

the fluid. The energy-momentum tensor in eq.(8.4) does not

take into account any dissipative processes and therefore the equations

of motion expressed by eq.(8.1) refer to an ideal fluid.

We now project eq.(8.1) on the direction of the 4-velocity, that

is, we multiply eq.(8.1) by ![]() and use the fact that

and use the fact that

![]() which implies

which implies

By the first law of thermodynamics:

in which ![]() is the temperature and

is the temperature and ![]() the entropy per unit volume, together with the continuity equation,

eq.(9.1), it follows that eq.(9.2) can be rewritten

as:

the entropy per unit volume, together with the continuity equation,

eq.(9.1), it follows that eq.(9.2) can be rewritten

as:

where the derivative

![]() means differentiation along the world line

means differentiation along the world line ![]() of the fluid

element concerned and the interval

of the fluid

element concerned and the interval

![]() . Eq.(9.4) means that the

fluid is adiabatic.

. Eq.(9.4) means that the

fluid is adiabatic.

Let us now project eq.(8.1) on a direction orthogonal to

![]() . To do so, note that the tensor

. To do so, note that the tensor

![]() is perpendicular to

is perpendicular to ![]() . We can multiply

eq.(8.1), that is

. We can multiply

eq.(8.1), that is

![]() ,

by this tensor and find

,

by this tensor and find

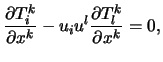

|

(9.5) |

which is indeed a perpendicular vector to ![]() . Expansion

of this relation results in the equation:

. Expansion

of this relation results in the equation:

which is the 4-dimensional Euler equation. The three spatial components constitute the relativistic Euler equation:

where

![]() is the flow velocity and

the Lorentz factor

is the flow velocity and

the Lorentz factor ![]() is given by

is given by

![]() . The time component of eq.(9.6) is implied

by the other three. In the case of isentropic flow, that is, when

. The time component of eq.(9.6) is implied

by the other three. In the case of isentropic flow, that is, when

![]() , and assuming the flow to be steady,

the spatial components of eq.(9.6) give

, and assuming the flow to be steady,

the spatial components of eq.(9.6) give

Scalar multiplication by

![]() leads to

leads to

![]() which implies that along

any streamline the quantity

which implies that along

any streamline the quantity

This is the relativistic version of Bernoulli's

equation.![]()