Next: §24 Steady simple waves Previous: IV Stability of non-straight Contents

Let us describe briefly the exact solution of the equations of

hydrodynamics for plane steady flow depending on one angular variable

![]() only. This problem was first investigated by Prandtl and

Meyer in 1908 (Courant & Friedrichs, 1976; Landau & Lifshitz, 1995) for the case in which relativistic

effects were not taken into account. The full relativistic solution to

the problem is due to Kolosnitsyn & Stanyukovich (1984).

only. This problem was first investigated by Prandtl and

Meyer in 1908 (Courant & Friedrichs, 1976; Landau & Lifshitz, 1995) for the case in which relativistic

effects were not taken into account. The full relativistic solution to

the problem is due to Kolosnitsyn & Stanyukovich (1984).

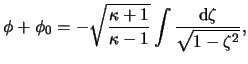

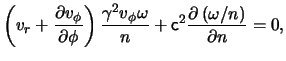

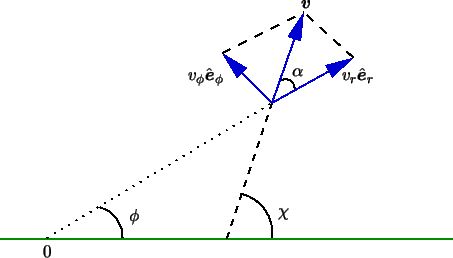

For this case, Euler's equation, eq.(9.6) and the continuity equation, eq.(9.1) can be written:

where

![]() and

and ![]() are the components

of the velocity in the radial and azimuthal directions respectively.

Eq.(23.3) is the Bernoulli equation, eq.(9.8), for

this problem.

are the components

of the velocity in the radial and azimuthal directions respectively.

Eq.(23.3) is the Bernoulli equation, eq.(9.8), for

this problem.

Using the definition of the speed of sound, eq.(11.3), in eq.(23.2) with the aid of eq.(23.3) it is found that:

On the other hand, differentiation of

![]() with

respect to the azimuthal angle

with

respect to the azimuthal angle ![]() and using eq.(23.3),

gives:

and using eq.(23.3),

gives:

Multiplication of eq.(23.4) by

![]() and

substracting this from eq.(23.5) gives:

and

substracting this from eq.(23.5) gives:

On the other hand, Bernoulli's equation, eq.(23.3), together with the value of the specific enthalpy for a polytropic gas given in eq.(12.4), can be rewritten

in which it has been assumed that at some definite point,

the flow velocity vanishes and the speed of sound has a value ![]() there. It is always possible to make the velocity zero at a certain

point by a suitable choice of the system of reference.

there. It is always possible to make the velocity zero at a certain

point by a suitable choice of the system of reference.

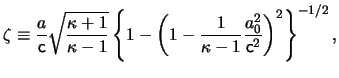

Eqs.(23.6)-(23.7) can be solved in terms of

![]() and

and ![]() :

:

Because

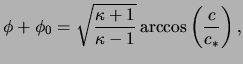

![]() , eq.(23.1) gives the required solution (Kolosnitsyn & Stanyukovich, 1984):

, eq.(23.1) gives the required solution (Kolosnitsyn & Stanyukovich, 1984):

This equation gives the speed of sound as a function of the

azimuthal angle. From eqs.(23.8)-(23.9) it follows that

the radial and azimuthal velocities can be obtained as a function of the

same angle ![]() . Because of this, all the remaining hydrodynamical

variables can be found. The sign in eq.(23.11) can be chosen

to be negative by measuring the angle

. Because of this, all the remaining hydrodynamical

variables can be found. The sign in eq.(23.11) can be chosen

to be negative by measuring the angle ![]() in the appropriate

direction and we will do that in what follows.

in the appropriate

direction and we will do that in what follows.

Let us consider now the case of an ultrarelativistic gas and integrate eq.(23.11) by parts, to obtain:

For the case of an ultrarelativistic gas, the speed of sound

![]() is given by eq.(12.6). In other words, this velocity is

constant and so the integral in eq.(23.12) is a Lebesgue integral.

Since this integral is taken over a bounded and measurable function over

a set of measure zero, its value is zero.

is given by eq.(12.6). In other words, this velocity is

constant and so the integral in eq.(23.12) is a Lebesgue integral.

Since this integral is taken over a bounded and measurable function over

a set of measure zero, its value is zero.

Using eqs.(23.8)-(23.9) and eq.(23.12) the desired solution is obtained (Kolosnitsyn & Stanyukovich, 1984; Königl, 1980):

for an ultrarelativistic equation of state of the gas.

For the classical case, in which

![]() ,

eq.(23.11) gives for a polytropic gas with polytropic index

,

eq.(23.11) gives for a polytropic gas with polytropic index ![]() :

:

|

|

|

where

| |

|

|

|

and so, the required solution is (Kolosnitsyn & Stanyukovich, 1984):

| |

|

(23.15) |

where the speed of sound ![]() has been rewritten as

has been rewritten as ![]() to be consistent in the non-relativistic case. The critical

velocity of sound

to be consistent in the non-relativistic case. The critical

velocity of sound ![]() is given by (Landau & Lifshitz, 1995):

is given by (Landau & Lifshitz, 1995):

The value for the velocities can thus be calculated from

eq.(23.1) and eq.(23.9) with

![]() :

:

Some important inequalities must be satisfied for the flow under

consideration. First of all, eq.(23.11) together with

eq.(12.4) and the first law of thermodynamics imply that

![]() . Using this inequality

and the fact that

. Using this inequality

and the fact that

![]() combined with the first law of thermodynamics, it follows

that

combined with the first law of thermodynamics, it follows

that

![]() . Also, using

eqs.(23.8)-(23.9) it follows that

. Also, using

eqs.(23.8)-(23.9) it follows that

![]() and

necessarily

and

necessarily

![]() .

.

On the other hand, the angle ![]() that the velocity vector makes

with a definite axis is related to the velocity and the azimuthal angle

that the velocity vector makes

with a definite axis is related to the velocity and the azimuthal angle ![]() by:

by:

as it is seen from fig.(IV.1). Thus, since the ![]() component of Euler's equation, eq.(9.6) implies that:

component of Euler's equation, eq.(9.6) implies that:

it follows that

![]() .

.

|

In other words, we have proved that for the flow for which we are concerned, the following inequalities are satisfied:

A flow with these properties is often described as a rarefaction wave (Landau & Lifshitz, 1995) and we will use this name in what follows.

Another, very important property of this rarefaction wave is

that the lines at constant ![]() intersect the streamlines at

the Mach angle, that is, they are characteristics. Indeed, from

fig.(IV.1), it follows that the angle

intersect the streamlines at

the Mach angle, that is, they are characteristics. Indeed, from

fig.(IV.1), it follows that the angle ![]() between the

line

between the

line

![]() and the velocity vector

and the velocity vector

![]() is given by

is given by

![]() .

Using eqs.(23.8)-(23.10) it follows that this relation can

be written as eq.(11.20). Because all quantities in the problem

are functions of a single variable, the angle

.

Using eqs.(23.8)-(23.10) it follows that this relation can

be written as eq.(11.20). Because all quantities in the problem

are functions of a single variable, the angle ![]() , it follows

that every hydrodynamical quantity is constant along the characteristics.

, it follows

that every hydrodynamical quantity is constant along the characteristics.

Sergio Mendoza Fri Apr 20, 2001