Next: V Shock-cloud collisions Previous: §24 Steady simple waves Contents

Let us now use the results obtained in sections §23 and §24 and apply them to the case of jets that are curved due to any mechanism, for example the interaction of the jet with a cloud as was discussed in Chapter III.

The greatest danger occurs when a jet is bent and forms internal shock waves. This is because, after a shock, the normal velocity component of the flow to the surface of the shock becomes subsonic and the jet flares outward. Nevertheless, as we have seen in section §24, the shock that forms when gas flows around a curved profile (such as a bent jet due to external pressure gradients) does not start from the boundary of the jet. It actually forms at an intermediate point to the flow. In other words, it is possible that, if a jet does not bend too much the intersection of the characteristic lines actually occurs outside the jet and the flow can curve without the production of internal shocks.

As we have seen in section §24 the Mach angle of the flow, relativistic and non-relativistic, does not remain constant in the bend -see for example eq.(24.7) and eq.(24.10). The Mach number monotonically decreases as the bend proceeds.

Eq.(24.7) and eq.(24.10) imply that:

where

As was mentioned above, if the jet is sufficiently narrow, it appears

that it can safely avoid the formation of an internal shock. However,

differentiation of eq.(25.1) with respect to the angle the

velocity vector makes with the ![]() axis, that is the deflection

angle

axis, that is the deflection

angle ![]() , implies that:

, implies that:

with

The Mach number ![]() is given by eq.(11.22) and

eq.(11.20) respectively. As the Mach number

is given by eq.(11.22) and

eq.(11.20) respectively. As the Mach number

![]() , then the derivative

, then the derivative

![]() . This means that the rate of change of the

Mach angle with respect to the deflection angle grows without limit

as the Mach number decreases and reaches unity. On a bend, the Mach

number decreases and care is needed, otherwise characteristics will

intersect at the end of the curvature. There is only one special shape

for which this effect is bypassed and this occurs when the increase

of

. This means that the rate of change of the

Mach angle with respect to the deflection angle grows without limit

as the Mach number decreases and reaches unity. On a bend, the Mach

number decreases and care is needed, otherwise characteristics will

intersect at the end of the curvature. There is only one special shape

for which this effect is bypassed and this occurs when the increase

of ![]() matches exactly with the increase of

matches exactly with the increase of ![]() (Courant & Friedrichs, 1976), but of course, this is quite a unique case. It appears

however, that whatever the thickness of the jet it cannot be bent more

than the point at which

(Courant & Friedrichs, 1976), but of course, this is quite a unique case. It appears

however, that whatever the thickness of the jet it cannot be bent more

than the point at which

![]() exceeds the rate of change of

exceeds the rate of change of ![]() with respect to the bending

angle

with respect to the bending

angle ![]() . In other words,

. In other words,

![]() .

From this last inequality and eq.(25.3) a value of the Mach

number can be obtained (Icke, 1991):

.

From this last inequality and eq.(25.3) a value of the Mach

number can be obtained (Icke, 1991):

If the Mach number in the jet decreases in such a way that the

value ![]() is reached, then a terminal shock is produced

and the jet structure is likely to be disrupted. It is important to note

that this terminal shock is weak since

is reached, then a terminal shock is produced

and the jet structure is likely to be disrupted. It is important to note

that this terminal shock is weak since

![]() and so,

it might not be too disruptive. Nevertheless, this monotonic decrease

of the Mach number makes the jet to flare outwards, even if the terminal

shock is weak.

and so,

it might not be too disruptive. Nevertheless, this monotonic decrease

of the Mach number makes the jet to flare outwards, even if the terminal

shock is weak.

Let us now calculate an upper limit for the maximum deflection angle for which jets do not produce terminal shocks. In order to do so, we rewrite eq.(25.1) in the following way:

To eliminate the constant ![]() from all our relations,

we can compare the angle

from all our relations,

we can compare the angle ![]() evaluated at the minimum possible

value of the Mach angle

evaluated at the minimum possible

value of the Mach angle

![]() with

with ![]() evaluated at its maximum value

evaluated at its maximum value

![]() . In other words,

the angle

. In other words,

the angle

![]() defined as:

defined as:

is an upper limit to the deflection angle. Jets which bend more

than this limiting value

![]() develop a terminal

shock and the jet will flare outward.

develop a terminal

shock and the jet will flare outward.

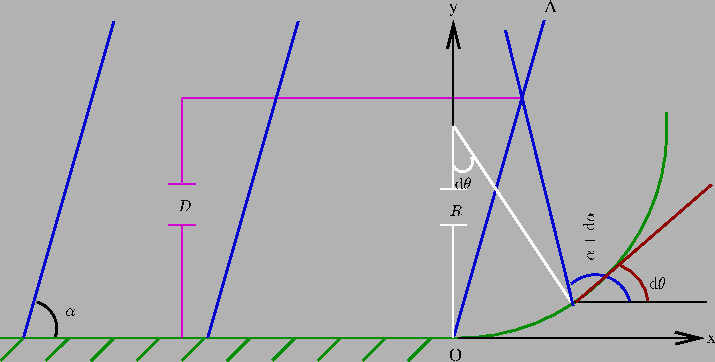

This upper limit however, does not mean that the jet is immune from developing an internal shock if it is bent by a smaller angle. Indeed, let us suppose that the jet bends and that the curvature it follows is a segment of a circle as it is shown in fig.(IV.3). According to the figure, the equation of the characteristic OA that emanates from the point O, where the curvature starts is:

|

Once the flow has curved

![]() degrees, the

characteristic at this point is given by:

degrees, the

characteristic at this point is given by:

where R is the radius of curvature of the circular

trajectory. The intersection of this characteristic and that given by

eq.(25.8) occurs when the ![]() coordinate has a value:

coordinate has a value:

Substitution of eq.(25.3) gives (Icke, 1991):

Using eq.(25.6) and eq.(25.9) it is possible to make a

plot in which two zones separate the cases for jets which develop shocks

at the onset of the curvature, and the ones that do not. Indeed, we can

plot the ratio of the width of the jet ![]() to radius of curvature

to radius of curvature

![]() as a function of the difference

as a function of the difference

![]() between the deflection angle

between the deflection angle ![]() and the maximum deflection

angle

and the maximum deflection

angle

![]() , as is shown

in fig.(IV.4).

, as is shown

in fig.(IV.4).

Jets for which the ratio ![]() lies below the curve do not

develop any shocks at all. For example, consider a jet with a given Mach

number for which its ratio

lies below the curve do not

develop any shocks at all. For example, consider a jet with a given Mach

number for which its ratio ![]() is given. As the width of the

jet increases (or the radius of curvature of the profile decreases), it

comes a point in which a shock at the onset of the curvature is produced.

In the same way, jets with a fixed ratio

is given. As the width of the

jet increases (or the radius of curvature of the profile decreases), it

comes a point in which a shock at the onset of the curvature is produced.

In the same way, jets with a fixed ratio ![]() for a given Mach

number which are initially stable -so that they lie below the curve-

can develop a shock at the beginning of the curvature by increasing

the bending angle of the curve.

for a given Mach

number which are initially stable -so that they lie below the curve-

can develop a shock at the beginning of the curvature by increasing

the bending angle of the curve.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.85]{fig.4.4.a.eps}](img757.png)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.85]{fig.4.4.b.eps}](img758.png)

|

The relativistic Mach angle is smaller for a given value of the velocity of the flow than its classical counterpart as it was proved in Section §11 -see for example fig.(II.2). This fact is extremely important when analysing the possibility of the intersection of different characteristics in a jet that bends. For a relativistic flow, the characteristics, which make an angle equal to the Mach angle to the streamlines, are always beamed in the direction of the flow. Thus, when a jet starts to bend the possibility of intersection between some characteristic line in the curved jet and the ones before the flow has curved, become more probable than their classical counterpart.

This difference results in a severe overestimation of the maximum

bending angle

![]() . For example, Icke (1991)

used the classical analysis in the discussion of the generation of

internal shocks due to bending of jets. Using the classical equations

described above, but with a polytropic index

. For example, Icke (1991)

used the classical analysis in the discussion of the generation of

internal shocks due to bending of jets. Using the classical equations

described above, but with a polytropic index

![]() ,

then

,

then

![]() .

This is much greater than the value of

.

This is much greater than the value of

![]() obtained with a full relativistic treatment

which is impossible.

obtained with a full relativistic treatment

which is impossible.

The analysis made by Icke (1991) is important for jets in which the microscopic motion of the flow inside the jet is relativistic, but the bulk motion of the flow is non-relativistic.

Sergio Mendoza Fri Apr 20, 2001